In Person Secret Santa Allocation - An overly complicated take

How it started

On a random Friday, amid random discussions, Bibek dae suggested that we have some sort of decentralized protocol to allocate names for Secret Santa this year.

I was certain that some implementation of this must exist and indeed that was true. I found one by nicholaspun/secret-santa and another by kielejocain/decentralized-santa. It is also possible to use many of the online services which promise to do the allocation for you and email everyone their secret santa. This delegates the task to a trusted third party which may not be that much of an issue unless you really wanna be verifiably fair about the allocations. The real concern is the sensitive contact information we are sharing with those services, and the privacy risks that come with it.

Since all of us would be in person, I set out to find a method that would involve little to no tech and would be simple enough to explain in a few minutes. After all, the beauty of cryptography is that often someone fully comprehends the algorithm and all its steps and is still amused by the implications.

The Naive Approach

The easiest idea is to draw names from a bowl. We make chits with each person’s name that are then picked randomly. The result, however, is a permutation and not a derangement as we desired. A derangement is a permutation where no element remains in its original place (i.e., no one is their own Santa). We can simply repeat if someone objects and can prove that they got their own name by revealing their chit. On average, how many times do we need to repeat this before no one is assigned themselves as their own Secret Santa?

Let us suppose we have \(n\) people.

The number of possible permutations is \(n!\) (n factorial).

The number of possible derangements is \(!n\) where \(!n\) can be defined recursively as 1

\[!n = (n-1)(!(n-1) + !(n-2))\]The probability of getting a derangement is thus \(\frac{!n}{n!}\).

For some concrete examples:

- For n=4: !4 = 9, so probability = 9/24 ≈ 0.375

- For n=5: !5 = 44, so probability = 44/120 ≈ 0.367

- For n=6: !6 = 265, so probability = 265/720 ≈ 0.368

As n increases, this value converges to \(\frac{1}{e} \approx 0.368\).

We can get the average number of rounds needed by computing the expected value of the random variable with a geometric distribution. If the success probability is \(p\), then the expected value is given by2

\[E(\mathbb{X}) = \frac{1}{p}\]The average number of rounds needed will be then \(e\) which is approximately \(2.71828\). It’s not a lot of retries but still leaves room for improvement. After all, it would be satisfying to have a valid allocation in the very first attempt. Also, would it not be awesome to have a way to ensure that if someone does not bring a gift, we can identify them without revealing other allocations.

Figuring out Requirements

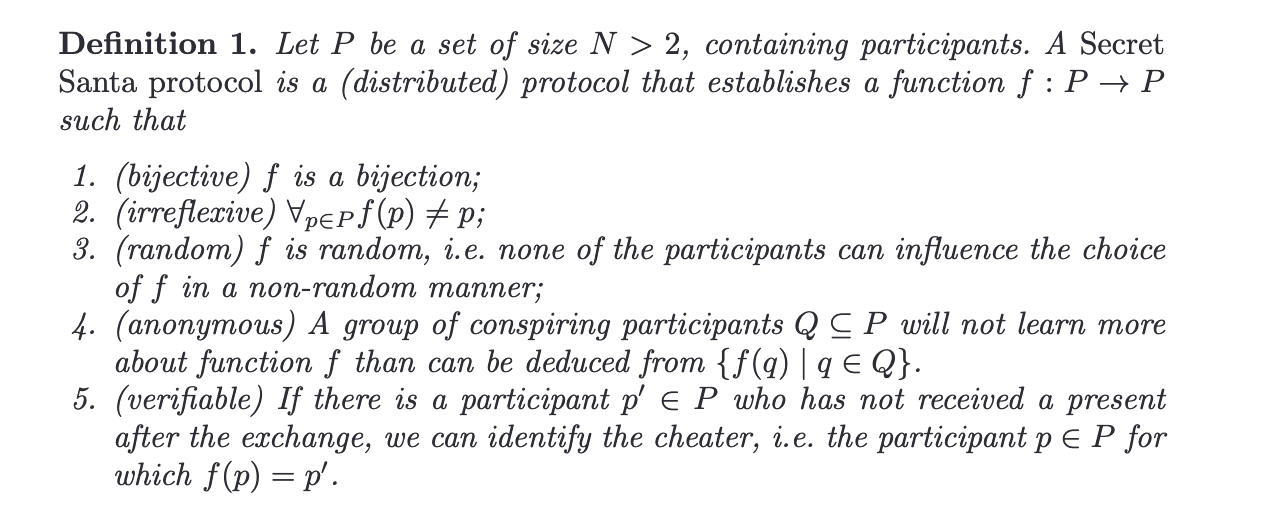

Before we go on exploring further ideas, it might be helpful to elucidate the exact requirements. Sjouke Mauw et al. lay out the following requirements in the paper Security Protocols for Secret Santa. 3

The first requirement of \(f\) being a bijection is composed of two parts, f must be surjective and injective. The first of these two properties makes sure no one is left out and each person is assigned to someone as their Secret Santa. The second part ensures that each person only has to gift one person and on the same note, each person only gets a gift from one person.

The second requirement of irreflexivity ensures we are not assigned as our own Secret Santa. The third property of randomness ensures that the draws are fair and cannot be influenced. The fourth requirement of anonymity tells that no information about allocation should be revealed. For only two participants, we already know the allocation. However, this doesn’t invalidate requirement 4, as the allocation was already deducible from requirement 2.

The last requirement is what is missing from our naive scheme above. We want verifiability, i.e., the ability to identify the Secret Santa assigned to the party who didn’t get the gift.

A better Approach

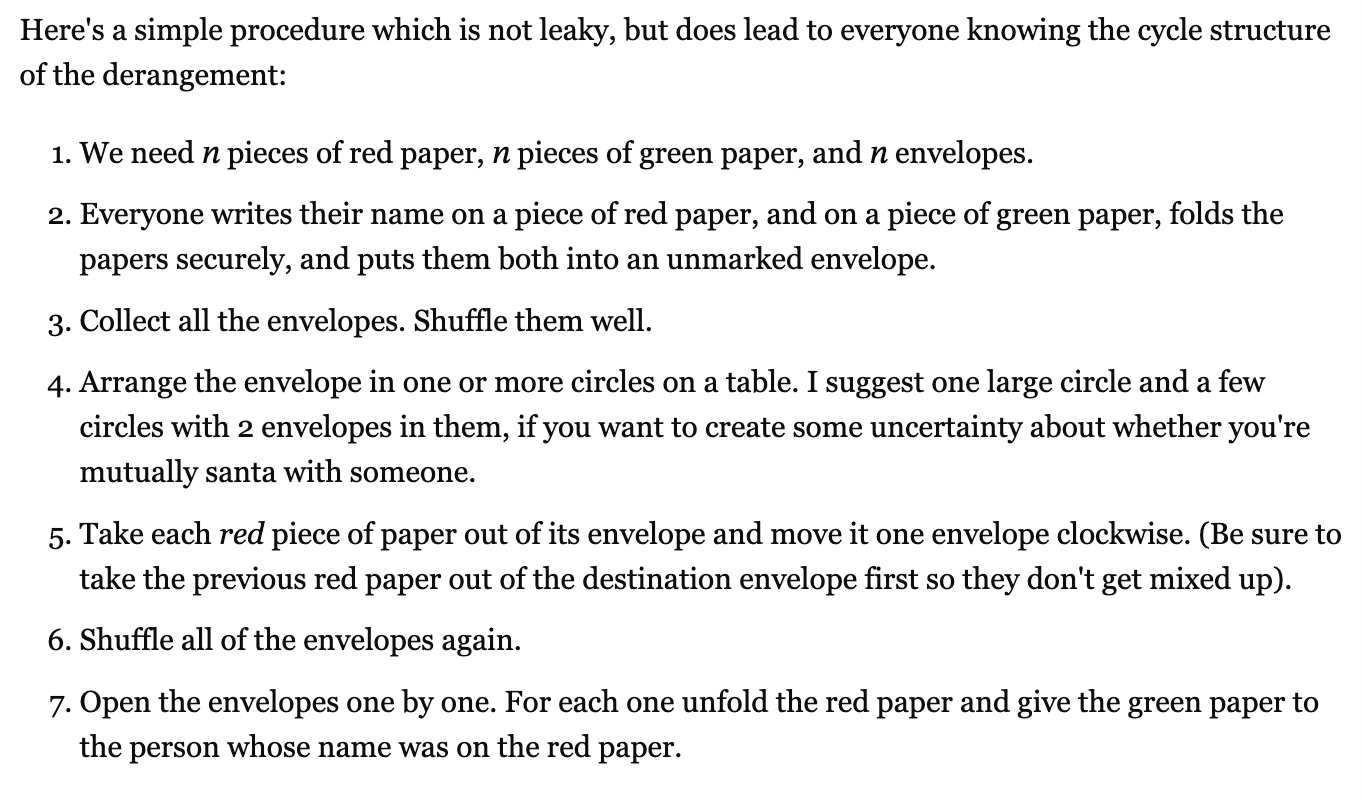

While looking for better algorithms, I stumbled upon the following algorithm by @hmakholm posted at Stack Exchange.

The above scheme is simple and works well. You get a perfect allocation in a single iteration. It’s also beneficial that everyone is involved. It still lacks verifiability which we will add by some clever use of tamper-proof packets.

Tamper-proof envelopes used to ensure verifiability in the Secret Santa allocation process

Adding Verifiability

To achieve this, we can use tamper-proof mailing packets.

After each person has seen their green paper, we collect it while still folded and place it in the envelope along with the red paper containing their name.

We place all of the envelopes in the packet and seal it. Everyone signs it, and then it is entrusted to a designated individual. At gift distribution, this person reproduces the sealed packet, allowing everyone to verify their signatures.

We have made another assumption here.

“People would love to learn who their Secret Santa is—but not if it risks everyone discovering they peeked”

If anyone does not receive a gift, the sealed packet can be opened to reveal the allocations and identify who was supposed to give the gift.

We go through the envelopes, pulling out only the green papers while leaving the red ones untouched, until we discover the identity of the person who sadly didn’t receive their gift. We can then pull the red paper from this very envelope to find the name of the culprit.

The Happy Path

If everyone has received a gift and there are no issues, we can have a small ceremony to destroy the information and ensure no one can know the allocations from the envelope. This is done by opening the envelope and taking out all the papers and shuffling them still folded.

You could even reuse the papers and envelopes for next year.

Future Works

-

Could any of these schemes be made to adapt elegantly when we have restrictions? For example, when we have restrictions on the possible assignments.

-

Can the verifiability be modularized and abstracted to decouple it from the specifics of secret santa problem?

-

Instead of tamper proof envelopes, we could use a box secured with n padlocks such that it can only be opened if everyone removes their lock. Given the existence of such a box, is there something clever that can be done?

Updates

This section will be updated with any new developments, corrections, or additional insights.